The Myth Of 1% Better Everyday

Takeaway Points:

Humans don’t improve exponentially; our skills and talents take time to develop.

When it comes to fitness, there is often a hard (physical) or soft (priority shift) limit to our growth because we can no longer put in the time and effort improvement requires.

The phrase “1% better everyday” isn’t about literally improving 1% every single day, it’s about putting in the concentrated and meaningful work to get better. It encourages people to build habits and routines that will lead them to long term success.

I’m sure you’ve heard the common line that progress is about searching for small consistent improvements over time - “1% better everyday” or something similar. For example, here’s James Clear on the topic.

I wanted to break through this common improvement myth, and why it can be, while well-intended, often a bit misguided.

Understanding Linear and Exponential Scaling

Linear Scaling

One thing that’s important to understand, is that it’s really hard for humans to naturally understand the difference between linear and exponential scaling.

A process which scales linearly is one in which improvement over time is represented by adding continuously. Let’s say that on day 1 you have $1, and each day you earn 1 additional dollar by working. By day 30, you have $30. By day 365, you have $365.

In linear scaling, each individual day doesn’t have much of an impact. If you take a day off in this process, for example, you still end up at the end of the year with $364. In a general sense, you still want to be putting in the effort because you’re still gaining money, but it stops feeling meaningful after a while, because the relative value of each individual day actually decreases the further along you are.

On day 1, you have $1. On day 2, you have $2. This represents a huge increase - a 100% increase in a single day! But then on day 3, you have $3 - ok, still a decent amount, but you’re only making a 50% increase now. On day 4, your relative increase drops to 33%. By day 365, the value of an additional day of work is just 1/365ths of your wealth, or about a fifth of a single percent. That sucks - at that point, you probably don’t feel much inclined to keep putting in the extra work - you’re still making more money, but it doesn't feel like it’s worth it.

This is the problem with linear scaling - it works well for a while, but after a certain point the relative change for a given unit of effort dwindles to almost nothing. This is what it feels like working a day job to put together savings, little by little, over a long period of time.

Exponential Scaling

Exponential scaling works, not by adding, but by multiplying. So long as the number is positive and greater than one, the result will continue to increase, and at a much more dramatic rate than with linear scaling - a rate that’s so dramatic, that it’s kind of unnatural for humans to wrap our heads around.

Let’s take the example above, but scale exponentially by a factor of 2. On day 1, you’ve got $1. On day 2, you have $2. Then $4, then $8 - and by day 365, you have - well, the number is $7.515336e+109. That’s scientific notation - how we display numbers so large that it’s impractical to write them out.

What that means is that if you take the number 1, add 109 zeros onto the end of that, and multiply it by 7.515336, that would be the amount of money you’d have - that’s well past the range of thousands, millions, or even billions. You can see that things scale VERY dramatically exponentially, to the extent that they quickly don’t mean very much - it gets hard to wrap our minds around. Let’s try the same thing with a much smaller number - let’s say %1, or 1.01.

That means that on day 1 you’d have $1, on day 2 you’d have $1.01, on day 3 you’d have $1.02, and so on - it develops much more slowly at first. By day 365, you’d be at $37.78 - still significantly worse than the linear example above, where you’d have $365 by the end of the year.

However, the value of exponential scaling is that the relative value of each further day of work stays the same, rather than decreasing - each day, you get %1 more, no matter what, which means that on day 365 you’re still feeling great for the effort you’re putting in, compared to the linear guy who’s thinking about quitting.

If we stretch this out even further, we can see the exponential scaling (even at this very low rate) start to catch up. If we extend this out to 2 years, the linear scaler now has $730 (if you stick it out every single day, even though it gets more exhausting), while the exponential scale now has $1427.58 - almost twice as much. If we extend this out to 3 years, the linear scaler now has $1095, while the exponential scaler now has $53,939.17 - 53 times as much. Extending it out to 4 years, the numbers become $1460 and $2,038,007.24, and extending it out to 5 years, the numbers become $1825 and $77,002,912.75. The linear scaler now has a couple thousand dollars, while the exponential scaler will soon be a billionaire.

Understanding the Difference

Many things in life scale linearly. For example, the amount of time you put into a hobby or pursuit scales linearly with time - you can put in a half hour today, a half hour tomorrow, and so on - over time, this adds up linearly.

At the same time, many other things in life scale exponentially - the stock market, inflation, various growth patterns in nature, and so on. Yet often, these things scale exponentially on very long time scales, such that we can’t really see that rapid growth in the short term.

The stock market, for example, returns about 7% per year on average - not bad at all, except that this means that it takes a lot longer to get off the ground and scale up than our example above, where we scale up every single day. The above example is essentially the equivalent of a single dollar invested over a time scale of a few thousand years - and I assume you’d be dead by the time you can collect, unless you’re a vampire or something.

The difference between linear and exponential scaling is not always clear at lower levels of iteration, where the exponential scaling hasn’t had the chance to really overtake its linear counterpart. Thus, in the beginning, linear scaling appears to have an advantage. This graph demonstrates that quite effectively.

The red line here represents linear growth, while the blue and green lines represent two different kinds of exponential growth. Both take longer to “ramp up”, but both SIGNIFICANTLY outpace the red line over time, by many orders of magnitude. You can ramp exponential scaling down to even a very very tiny percentage (like 1%) but over time, no matter what, it’s still going to overtake linear scaling in the long run.

Naturally, this difference is often demonstrated in various stories and fables - for example, asking whether you’d rather have a lump sum of X or some much smaller sum Y that doubles each day for a month, or something similar. The point of these stories is to explain that, while it initially seems to have a disadvantage, exponential scaling is hard to wrap our brains around and always superior in the long run.

How Do Human Abilities Scale?

Human abilities scale - well, obviously NOT exponentially. If I could get 1% better every day at squatting, then I would, starting out at a modest squat of 100lbs, currently be sitting at a squat of uhhh 100*1.01^(365*15) = 4.5658481e+25 after 15 years of consecutive training. Naturally, I’m nowhere near that - my personal best squat was 415lbs @ 198 a few years back, and the world unequipped record in that weight class is 804lbs.

Human beings simply don’t progress exponentially. Full stop.

The reality is that there are diminishing returns to effort, and that means that as you get better, you improve less and less over time as you approach a kind of limit, your personal “genetic limit”. I often want to point out that this is a bit of a misnomer - many of the people out there, excepting the world-record-setting best athletes of all time, can, to some extent, continue to improve.

The reality is that the limit is a soft one - sooner or later, some combination of injury, the fact that training takes up your entire life, or the fact that you get frustrated and simply don’t want to put in the effort, is going to cause you to reassess. You’ll decide to focus on other things in your life, or you’ve gotten a bit older and taken on more responsibilities. That’s a normal thing, and why athleticism tends to skew younger.

Human bodies DON’T scale exponentially - they scale more like a sigmoid function - a kind of graph in calculus that has a distinctive S-like shape. For the purposes of fitness, where it’s (generally) impossible to gain NEGATIVE strength, we generally omit the bottom half of the graph, thus making it look less like an S.

Sigmoid functions scale similar to exponential functions in terms of their initial speed - they grow rather rapidly from 0 in either a positive or negative direction. However, these functions are limited by some natural limit that they can approach but never quite touch - and as a result, after some initial exponential-like scaling, they quickly slow down to a VERY dramatic crawl.

As you can see, sigmoid functions have some characteristics of both exponential and linear ones - and become more linear (and flat) over time. This represents a human coming close to their potential - in fitness, or any skill really.

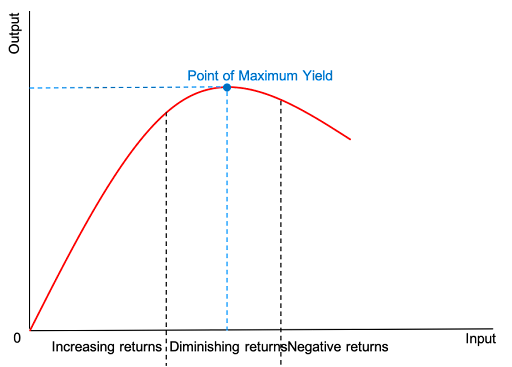

Common graphs of diminishing returns also posit the possibility of negative returns - the ability to overdo it so much that you end up decreasing your results. This is what would happen, for example, if you went into the gym and trained so hard that you injured yourself and had to take time off of training, or if you trained 10 hours a day but didn’t have time for a good sleep routine, or the ability to take care of everything else in your life.

So Why Do We Say 1% Better Every Day?

It’s really a good question - why DO we say that, if it’s simply not true? The reality of our efforts is that what we can put into an activity is linear (more time spent training - the classic “10,000 hours” rule), and what we get out of it is diminishing returns. We can keep putting in more and more training hours over more and more years of our lives, but sooner or later our progress will slow down to a crawl, and we WISH we could get 1% better on a consistent basis.

This isn’t something where I’m trying to put James Clear on blast here, for sure. I think his book Atomic Habits is one of the only truly good books about self-improvement out there in a sea of BS, and I recommend it highly.

In fact, there’s a very funny story - I once met him at a conference, and I technically owe him lunch because a snafu with the tablet-based ordering system ended up charging both our meals to his card. So if nothing else, go buy his book now so that I can pay him back.

However, at the end of the day, “1% better every day” is basically just a nice and catchy marketing line - it doesn’t have too much to do with the reality of getting better, I think.

Instead, the reality of getting better is that you have to put in the time, and you have to focus on making that time as high quality as possible. Train with exercises that have a high return on investment, like major compound lifts (squat, deadlift, bench, overhead, row), and focus on increasing your training volume slowly and steadily over time.

And the truth is that results DO slow down over time. After the first few years, results come so slowly that you need to accept that you’re going to be putting in a lot of hours without a ton of extra muscle mass or strength to show for it. The effort you put into fitness scales linearly - and like the guy on day 365 in the linear example above, it might not feel worth it for a measly 0.2%.

At the same time, the effort you put in starts to feel more effortless. When you’ve been training for ten years, training for another day feels natural to you. The process isn’t about “getting 1% better every day” - it’s about getting so used to the process that it becomes a part of you, that you can’t imagine your day without it, and so on. You can only become the best version of yourself if you set a goal and stick to it, putting in small but consistent amounts of effort over long periods of time.

Are you willing to commit to picking up a new language and practicing it for 10 years to see if you’re any good at it? Take on a new exercise habit? Learn a new professional skill? The most important thing is about learning to think in the long term - learning to love the process and the practice of getting a little bit better all the time, even if that percentage is constantly decreasing to a vanishingly small value per day.

There are a lot of things in that post that James Clear gets right - learning to be a master of anything means falling in love with the un-sexy bits - putting in consistent work, iterating on your process, learning from your mistakes, and sticking to it even when you feel like a failure.

However, that doesn’t mean you should expect to see 1% per day improvement, or any particular number for that matter - instead, it’s more about knowing that you can only put in the effort, and embrace whatever it is that you get out of it in return.

About Adam Fisher

Adam is an experienced fitness coach and blogger who's been blogging and coaching since 2012, and lifting since 2006. He's written for numerous major health publications, including Personal Trainer Development Center, T-Nation, Bodybuilding.com, Fitocracy, and Juggernaut Training Systems.

During that time he has coached hundreds of individuals of all levels of fitness, including competitive powerlifters and older exercisers regaining the strength to walk up a flight of stairs. His own training revolves around bodybuilding and powerlifting, in which he’s competed.

Adam writes about fitness, health, science, philosophy, personal finance, self-improvement, productivity, the good life, and everything else that interests him. When he's not writing or lifting, he's usually hanging out with his cats or feeding his video game addiction.

Follow Adam on Facebook or Twitter, or subscribe to our mailing list, if you liked this post and want to say hello!

Enjoy this post? Share the gains!

Further Reading:

Ready to be your best self? Check out the Better book series, or download the sample chapters by signing up for our mailing list. Signing up for the mailing list also gets you two free exercise programs: GAINS, a well-rounded program for beginners, and Deadlift Every Day, an elite program for maximizing your strength with high frequency deadlifting.

Interested in coaching to maximize your results? Inquire here. If you don’t have the money for books or long term coaching, but still want to support the site, sign up for the mailing list or consider donating a small monthly amount to my Patreon.

Some of the links in this post may be affiliate links. For more info, check out my affiliate disclosure.